The success of endodontics relies on the localization of the entire root canal system and its subsequent cleaning, shaping, and three-dimensional obturation. Several magnification systems have been advocated over the years. The most convenient and popular have been loupes with varying degrees of magnification.

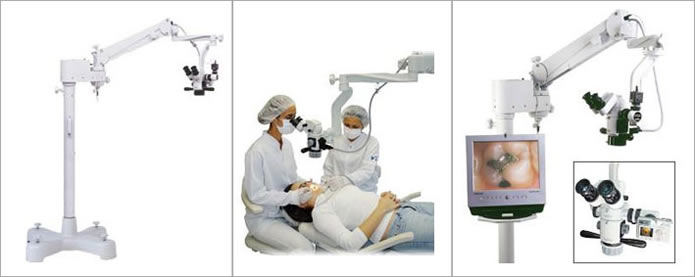

In several cases in which surgical endodontics is the treatment of choice, the increased magnification and illumination provided by the microscope allows enhanced visualization of the surgical field. This, in turn, allows for more efficient surgical technique and greater ability to achieve success in surgical endodontics.

Procedural errors can be greatly reduced, if not eliminated, and complicated cases become less so under the microscope.

Procedural errors can be greatly reduced, if not eliminated, and complicated cases become less so under the microscope.The introduction of the SOM is relatively new concept that is revolutionizing the way procedures are performed.

The SOM has a video camera attached.

Diagnosis:

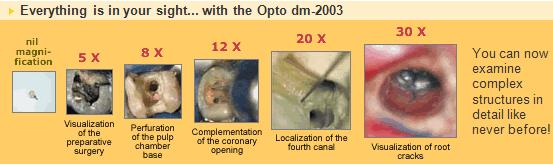

Diagnosis:The microscope is an excellent instrument to detect microfractures that cannot be seen by the naked eye or by loupes. Under 16 to 24 magnification and focused light, any microfracture can be easily detected. Methylene blue staining of the microfracture area assists this effort greatly.

A persistently painful tooth after endodontic therapy may be due to an untreated missing canal (eg, MB2 in a maxillary molar). Re-examination of the chamber at high magnification under the microscope may locate the missing canal.

The most important utility of the microscope in nonsurgical endodontics is locating hidden canals. The canal anatomy is extremely complex. All endodontic textbooks have information on molar teeth with three canals, premolars with two canals, and anterior teeth with one canal. Often, dental anatomy is not that predictable. What was considered a rare exception in the past has become a routine finding when using the microscope. Considering this as the benefit of using the microscope for endodontic procedures is obvious.

There are teeth where the canal bifurcates at 3 to 5 mm into the canal and in the maxillary second molar, where the MB and DB are in very close proximity of each other; the microscope is an invaluable tool in clearly detecting the bifurcation and the two separate canals.

With normal vision or low-power loupes, calcified canal in the pulp chamber is not detectable. When the calcified canal is looked at through the microscope at high magnification, the difference in the color and texture between the calcified canal and the remaining dentin can be easily seen.

Perforation does occasionally occur no matter how carefully the tooth is accessed for endodontic therapy. When a perforation occurs, the microscope is the key instrument to identify and evaluate the damaged site. The results of a careful inspection will be the basis for which the preparation of the perforation repair will be made. Briefly, the microscopic procedure is to place a matrix precisely, just outside of the perforation site (ie, just exterior of the root substance). The matrix can be calcium sulfate or resorbable collagen. After the matrix is placed, mineral trioxide aggregate is packed against the matrix. This procedure requires delicate and careful handling of the materials so as not to extrude, overfill, or underfill. The microscope is essential for this procedure.

With the more frequent use of nickel-titanium rotary files in general dentistry, the incidence of file separation within the canals has increased. When the file is broken at the apex, the microscope cannot be of help. If the file breaks within the coronal half of the canal, however, then the microscope is essential to guide the clinician to retrieve the broken files. In this manner, the broken file can be removed while minimizing the damage to the surrounding dentin.

It takes a simple step to see whether a canal is completely cleaned. Under the microscope, a small amount of sodium hypochlorite, a popular irri- gation solution, is deposited into the canal and observed carefully at high magnification. If there are bubbles coming from the prepared canal, then there is still remnant pulp tissue in the canal. In short, the canal needs more cleaning.